Introduction

Lillian Schwartz in her essay "The Art Historian's Computer" (Scientific American, April 1995, pages 106-11) suggested that the Droeshout portrait of Shakespeare, which appeared in the First Folio, may have been based on a portrait of Queen Elizabeth I. Some antistratfordians have seized upon Schwartz's article as somehow "proving" that the Droeshout engraving actually is a portrait of Queen Elizabeth. This is a stronger claim than Schwartz herself makes in the article (which is qualified with such words as "appears" and "perhaps" and "suggest"), but Schwartz fails to make a convincing case even for her qualified belief that the Droeshout may be based on a portrait of Queen Elizabeth.

The first part of this essay grew out of a request by a reporter for comments on Schwartz's article. I pointed out a number of factors that made her argument untenable, and later posted my comments on the humanities.lit.authors.shakespeare newsgroup. That should have settled the matter, but some members of the newsgroup asked me to supply my own images so they could better judge for themselves. Therefore, in the second part of this essay, I have tried to apply Schwartz's methods as fairly as I could, and I have included a number of images that will show just how dissimilar the Droeshout and Gower's portrait of Elizabeth are; I have concentrated on those areas that, according to Schwartz, "match perfectly" on both portraits. Unfortunately, Schwartz's article is not available online, so readers interested in further evaluating her claims may wish to track down the April 1995 issue of Scientific American.

Schwartz believes that the Droeshout Shakespeare is so similar to the

"Armada" portrait of the queen in Britain's National Portrait Gallery (which is generally considered either to have been painted by George Gower or to be based on a similar painting by him) that it must have been traced from

some lost cartoon of the queen that was itself extremely similar to the

Gower. Her argument assumes that the features of Queen Elizabeth's face

were portrayed consistently in all instances, and that each portrait of

her was more like all the other portraits of her than any of them was like

any portrait of anybody else. Instead of assuming this, it might have

been useful if she had made some attempt to prove it. Schwartz could have

examined a substantial sample of the surviving depictions of Queen

Elizabeth from the 16th and 17th Centuries. She could have used her

techniques of flipping, digitizing, and scaling on these portraits in

order to discover whether the features of Queen Elizabeth were indeed

consistently portrayed. She could then have looked at contemporary

portraits of other people, and perhaps she could have learned whether it

was the case that all portraits of Elizabeth were more like each other

than any of them were like those of other people, or whether the variation

within the Elizabeth set was greater than the variation between some

portraits of Elizabeth and some portraits of other people. If she had

done the research, then there might be reason to take her argument

seriously, but she did not.

It is also surprising that she does not appear to have compared the

Droeshout with the other depiction of Shakespeare that has the strongest

claim to authenticity: the effigy in Shakespeare's monument in Stratford's

Holy Trinity Church, a work that clearly resembles the Droeshout in many

important respects. As M. H. Spielmann wrote in his classic study

"Shakespeare's Portraiture,"

In any event, the one portrait that Schwartz did compare with the

Droeshout print does not seem a very good match. I do not have Schwartz's

practice in her techniques, but with the aid of a magnifying glass and a ruler,

I have examined her statements and the images in her article, and I have

found significant discrepancies between what she claims to have shown and

what the images themselves reveal. [Note: when I use the words "left" and

"right" in discussing the portraits, I am referring to the viewer's left

and right, not the subject's: thus, although part of each subject's left

ear is visible in the Droeshout and Gower, the ears are on the viewer's right side

of the portraits.]

By flipping through a single book that I happened to have on hand, S.

Schoenbaum's Shakespeare: The Globe and the World (Folger Shakespeare

Library, 1979), I have found a number of contemporary depictions of Queen

Elizabeth that show a person with a sharper chin than appears in either

the Stratford bust or the Droeshout print (Schoenbaum pp. 96, 98, 101,

106); the Gower portrait that impressed Schwartz also has a sharper chin

than is found in the Stratford bust and the Droeshout. Moreover, Queen

Elizabeth has relatively wider and more prominent cheekbones than

Shakespeare in these images: Elizabeth and Shakespeare would therefore

seem to have had different skulls -- yet Schwartz maintains that the

"curvature of the faces match perfectly." Don't take my word for it:

follow the curvature on the left side of the queen's face in the Gower

(Schwartz's illustration "a"): notice that just below her left cheekbone

the line curves in: there is no such concavity in the Droeshout; obviously

the curvatures do not "match perfectly."

One of the most distinctive features of the Droeshout is Shakespeare's

extraordinary forehead. The forehead is not only quite high, but it also

has, as Schwartz notes, a rather bulbish appearance. The bulbishness seems

to be the result not of the location of the right hairline, as Schwartz

believes, but rather of the circular hatching in the Droeshout. In any

event, the size of the forehead is consistent with the Stratford effigy

but very unlike the Gower portrait, in which Elizabeth's forehead seems to

slope back, while Shakespeare's is more perpendicular in both the

Droeshout and the Stratford effigy. Once again, Elizabeth seems to have a

different skull than Shakespeare.

As it is, Schwartz manages to exaggerate the extent of the resemblances

between the Gower and the Droeshout by the scaling she chose. The major

part of her article is devoted to showing that the Mona Lisa resembles a

Leonardo self-portrait. Schwartz explains her procedure: "we scaled the

images by giving them the same distance between the centers of the

pupils." One might assume that the same procedure was used in the

Droeshout and Gower portraits, but in fact the interpupillary distance in

the Gower is substantially greater than in the Droeshout. The two images

are thus not properly scaled according to Schwartz's own methods. What

then was the principle for scaling?

Schwartz mentions in her discussion of the Mona Lisa that once she had

scaled on the basis of interpupillary distance, she found that "the

distance between the inner corners of the eyes, one of the most individual

characteristics of a face, matched to within 2 percent." That is to say,

if we scale two portraits on the basis of interpupillary distance and then

we find that the distance between the inner corners of the eyes is almost

the same, then (so her argument goes) we have reason to believe that we

are dealing with a common face. As it happens, despite the disparity

between the interpupillary distances of the Droeshout and the Gower, the

distances between the inner corners of the eyes is extremely close -- so

close that I suspect that this was the basis of Schwartz's scaling. If

so, then, if we employ the sort of reasoning Schwartz used in her

discussion of Leonardo, all significant disparities should be evidence

that the two images are of different faces.

It's not just that the interpupillary distance is significantly different.

If we look at the images in her article, we note that the top of the

cranium in the Droeshout has been cut off; on the other hand, the queen's

chin is lower on the page than Shakespeare's. Thus the queen has

proportionately more of her head below the cheekbones than Shakespeare and

less of her head above the cheekbones. This gross difference in

proportions is consistent with other portraits of both the queen and

Shakespeare, and it is further evidence that the Gower and Droeshout are

portraits of different people.

Schwartz also exaggerates the apparent similarities by shifting the

queen's image within the frame. Lay a straightedge or a ruler across the

series of illustrations, and align it with the bottom of the queen's mouth

(a feature that doesn't change). You will see that the queen's head is

set higher in "a" than in "b," and higher in "c" than in "a." Why does

Schwartz do this? Remember her claim that the chins of the two images

match. I have said that Shakespeare's chin is more rounded, while the

queen's is sharper. In picture "b" Schwartz sets the queen's head lower

in the frame and then attaches Shakespeare's rounder chin; the effect is

to give the impression that the two chins are more similar than they

actually are. Follow the left curve of the chin in "b" and see how rough

the curve is compared to the smooth line in "a."

A close comparison of the images suggests that while Droeshout and the

Gower faces are similarly (but not identically) oriented, and they both

have rather high foreheads (though Shakespeare's is notably higher than

Elizabeth's), the noses don't match (Elizabeth's is narrower and seems to

be curved while Shakespeare's is longer and straighter); the mouths don't

match (more on this later); the eyebrows don't match (the queen's eyebrows

are higher above her eyes than Shakespeare's are above his); the eyes

don't match (the queen's eyes are open wider, and the pupils of her

eyes are more centered, while the pupils of Shakespeare's eyes are more to the right);

the ears don't match (and the distance between the ear and

nose is substantially greater in the Gower than in the Droeshout); and the

Queen, of course, has no facial hair. Could all of these features vary so

much if the Droeshout was produced by tracing something like the Gower?

Schwartz does not claim that Martin Droeshout in 1623 was familiar with

Gower's painting from some 50 years earlier. Rather, she believes that

some hypothetical lost cartoon of the Queen's face that closely resembled

the Gower portrait but was exactly the same size as the Droeshout must

have been his source, and that Droeshout worked by tracing this phantom

cartoon. Schwartz guesses that he did the left side of the face first,

and then he "shifted" the cartoon and did the right side of the face.

How then did the mouth get placed so far to the right? Look at the Gower:

the mouth is centered under the center of the nose. Look at the

Droeshout: the mouth is centered under the nostril. If Droeshout had

indeed been tracing, then the mouth would have been aligned with the nose

(if the mouth had been part of the hypothetical "left-side" tracing), or

else it would have been aligned with the jawline on the right (if it was

part of the hypothetical "right-side" tracing), but the Droeshout mouth is

much further to the right then this hypothetical "shift" would explain.

In any event, the mouth would not be where Droeshout put it if he had been

tracing as Schwartz imagines.

Schwartz's chief evidence for this hypothetical "shift" is what she calls

the "mystery line." How mysterious is this line? Spielmann concedes that

As I have said, Schwartz in her Scientific American article shown no

sign of having done the essential preliminary research that her argument

would seem to require. Even if she had been able to point out a number of

striking similarities between Gower's portrait of Queen Elizabeth and

Droeshout's print, it would be impossible to say whether those

similarities were significant unless Schwartz had shown that portraits of

Elizabeth generally shared the same features she noted in the Droeshout

and that these features could not be found in other portraits on other

people. However, even granting for the sake of argument that such

similarities might be interesting, we find that Schwartz has departed from

the procedures she used in the Leonardo matter, that she has shifted

images within the frame so that an illusion of greater similarity is

created, that she has in general exaggerated slight or forced similarities

and overlooked major differences between the images. In short, her

article does not provide the basis to reject the traditional view that the

Droeshout print is and was intended to be a portrait of William

Shakespeare of Stratford-on-Avon.

Note that Shakespeare's face is both longer and narrower than Elizabeth's. What this means is that there is no possible way to scale the faces so that they will be the same. If we make Elizabeth's proportionately larger, then while it may become as long as Shakespeare's, the disparity in the widths of the faces will only increase. If we make Shakespeare's face smaller in order to set the length of his head equal to Elizabeth's, the relative narrowness of his head will become even more pronounced.

There are a number of striking differences between the images that rule out Schwartz's notion that the Shakespeare image is based on a tracing of something very like the Elizabeth. To take one obvious example that Schwartz somehow overlooked, note Elizabeth's very sharp left cheekbone, and contrast it with the smooth curve of Shakespeare's.

Let us compare some of the individual features of the two faces.

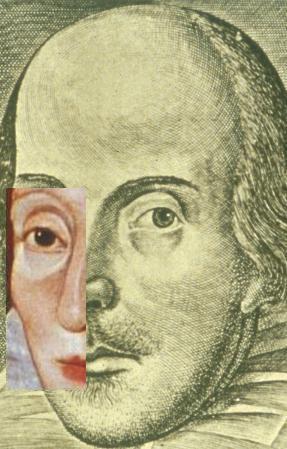

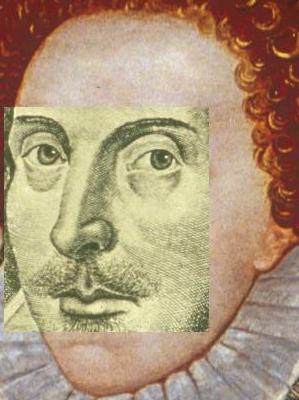

What happens if we take the "mask" of one face (the eyes, nose, and mouth) and superimpose it on the other? If Schwartz is correct in thinking that "the eyes, noses, and curvature of the faces match perfectly," then if we align the curvature of Shakespeare's mask to Elizabeth's face, and vice versa, we should hardly be able to tell any difference between the two. The actual results, however, are comical and grotesque.

On the left, Shakespeare wears the "mask" of Elizabeth. It was possible to make the outline of Elizabeth's face meet that of Shakespeare, but at the cost of great distortion to the face. Elizabeth "mask" is worn too low over Shakespeare's face; her eyes, nose, lips, and cheekbones are much too low, as is even more evident in the image on the right, where Shakespeare wears only part of her mask.

On the left, Elizabeth wears the mask of Shakespeare. While it was possible to "connect" the mask at two points on the left side of Elizabeth's face, the mask had to be set considerably higher than would have been comfortable; this is easier to see in the image on the right, where Elizabeth wears only half of the mask. Shakespeare's eye, nose, and mouth are all higher than Elizabeth's -- yet, despite Schwartz's claim that "the curvature of the faces match[es] perfectly," this is the only way we can make the outlines of the two heads connect. In the original portrait, the bottom of Elizabeth's nose is lower than the bottom of her ear. In this composite, however, the nose is much higher, and the bottom of the ear is nearly on the same level as the top of the upper lip. The eyes are set so high that if this really were a mask, Elizabeth would be unable to see through it.

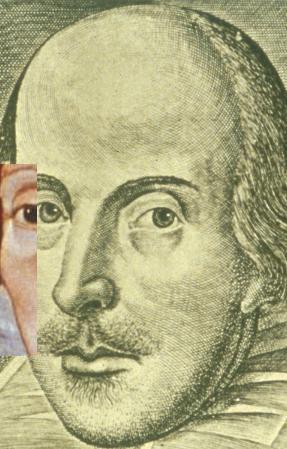

How greatly do the curvatures of the two faces match? Schwartz says they "match perfectly." What happens if we take a section of Elizabeth's "curvature" and superimpose it on Shakespeare's face?

If the "curvature of the faces" did indeed "match perfectly," then it should be possible to make the piece of Elizabeth's face fit seamlessly on Shakespeare's -- but it is simply impossible. In the left image, the lower part of the Elizabeth portion has been aligned with Shakespeare's jaw, but the upper part is grossly misaligned. In the right image, the upper part has been matched (as well as it could be) with Shakespeare's forehead and eye, but Elizabeth's jawline runs into his mouth.

Similar comparisons may be made by putting other parts of Elizabeth's head on Shakespeare's, or vice versa. I have concentrated on those areas where Schwartz claimed the resemblance was strongest. Readers are encouraged to print out this page and see for themselves whether the Droeshout image of Shakespeare is based on a tracing of something very much like the Gower portrait of Elizabeth.

Back to Shakespeare Authorship page.

Some Weaknesses of Schwartz's Discussion

Schwartz's methodology is puzzling. A reader might expect her to

demonstrate both the general validity of her procedure and the

conclusiveness of this particular instance, but she does neither.

Indeed, there isn't space in the few hundred words she devotes to the

matter for her to begin making a case; the most she can do is indicate

what such a case might look like, but the case she outlines is implausible

at best.

The bust, of course, professes to show what the Poet looked like when he

had put on flesh and bobbed his hair; yet in spite of the fact that

adipose tissue has rounded forms and filled up hollows, broadened masses

and generally increased dimensions -- we recognize that the perpendicular

forehead and the shape of the skull are very much the same in both; and we

further observe that whereas the Droeshout Print shows us chiefly the

width of the forehead across the temples, the full face of the bust gives

us the shape of the head farther back, across where the ears are set

on.... When all is said, the outstanding fact remains -- that the forms

of the skull, with its perpendicular rise of forehead, correspond with

those of the Stratford effigy; and this -- the formation of the skull --

is the definitive test of all the portraits. The Droeshout and the

sculpted effigy show the skull of the same man, who, in the engraving, is

some twenty years or so younger than him of the bust" (in Spielmann et

al., Studies in the First Folio, 1924: London: Oxford UP, pp. 26, 33).

Schwartz says nothing about any other image of Shakespeare (the Chandos

portrait might also have been worth a look) but tells us instead that she

compared the features of the Droeshout print with "those of the Earl of

Oxford and many other notables." She thus begins by assuming that William

Shakespeare of Stratford-on-Avon was not the author of the works that bore

his name, and that the "real author" must have been Oxford or some "other

notable." She gives us no reason to join her in this odd assumption.

Perhaps it was the desire of her mysterious unnamed "hosts" that she try

to link the Droeshout with anyone except Shakespeare. It is traditional in

scientific studies that are sponsored by interested parties that those

parties be named. Doesn't the reader have the right to know whether

Schwartz had been invited by some particular sect of antistratfordians

with an interest in bolstering their case?

[the Droeshout print] is singularly hard and overaccentuated in the jaw

line from the ear downwards, which has actually suggested to some of those

who ache at all costs to discredit the portrait as such, that it is a

mask. Yet this same line appears not only in many engravings, but in many

oil paintings of the period and since. For example, it is quite as marked

in Sir Joshua Reynolds's panting of Richard Burke, at which I was looking

not long ago, to take only one case out of scores. (Spielmann, 32)

Would Schwartz

consider the presence of such a line in these scores of other instances

equally mysterious, or equally strong "evidence" of sloppy tracing?

Face to Face: Shakespeare Is Not Elizabeth

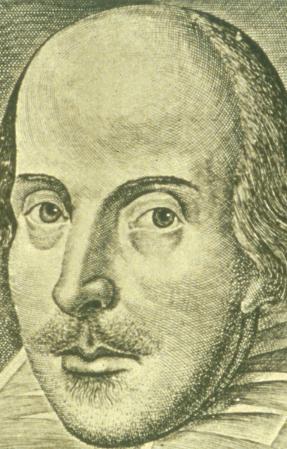

Here are the faces of Elizabeth (from the "Armada" portrait attributed to Gower) and Shakespeare (from the Droeshout engraving in the First Folio). I do not have Schwartz's tools, experience, or artistic ability, but with the aid of some readily available software, I have subjected images of the Droeshout and Gower portraits to manipulations similar to those done by Schwartz. Following the method used by Schwartz for her Leonardo study, I have "scaled the

images by giving them the same distance between the centers of the

pupils" (although the scaling may not be perfect, it's close enough). It is Schwartz's contention that "most of the lines in the Droeshout and the queen's portrait by George Gower are the same. The eyes, noses, and curvature of the faces match perfectly." A side-by-side comparison of certain elements of the faces shows that her contention is wrong.

Feature Shakespeare Elizabeth Comments

Left Eye

Schwartz says "the eyes ... match perfectly," but clearly this is not the case with the left eyes. Shakespeare's eye is more widely open and is looking more toward the viewer's right. Nor is it true, as Schwartz says, that "the curvature of the faces match[es] perfectly. Note the deep indentation in the outline of the face just under Shakespeare's eye, and contrast that with the outline in Elizabeth's image. Right Eye

It is also not true that the right eyes "match perfectly." Note that Shakespeare's brow is darker and lower, and that the under lid is both narrower and deeper than Elizabeth's. Shakespeare's eye is looking more toward the viewer's right than Elizabeth's.

Nose

Nor is it true that the noses "match perfectly." Shakespeare's nose is thicker than Elizabeth's; his nostril is more highly arched. If you compare the left line of each nose as it descends from the eye, you will notice that Shakespeare's breaks sharply to the left as it nears the tip, while Elizabeth's is much straighter.

Mouth ![]()

![]()

Although Schwartz doesn't comment on the mouths of the portraits, they do not match perfectly either. Both mouths are "cupid's bows," but Shakespeare's is fleshier. Trace the line between upper and lower lip in each image. Elizabeth's is almost a smooth curve; Shakespeare's is much more "M"-shaped, as the middle of the upper lip hangs over the lower. Now trace the bottom of the lower lip. Elizabeth's is a smooth curve; Shakespeare's is more squared. The Droeshout mouth could not have been traced from any hypothetical "cartoon" that had the features of the Gower portrait.

Conclusion

Given the many qualifications with which Schwartz advanced her case, it is surprising that some readers have decided that she had succeeded in proving that the Droeshout engraving of Shakespeare is "really" a portrait of Queen Elizabeth. A careful examination of her Scientific American article reveals so many problems with her brief discussion and the accompanying images that her account of the Droeshout's derivation from a portrait of the queen may be rejected. Nevertheless, one might still have believed that she had a point, even if had been poorly advanced, and so it was useful to try to apply her techniques more consistently than she had. The above images are the result. When the two images are scaled according to the distance between the centers of the pupils (as Schwartz did in the Leonardo part of her article), it is impossible to match the faces or their components. Nor would changing the scaling help the matter, because each image is larger than the other in some aspects but smaller in others, and rescaling would make some parts of the image into closer fits while making others even worse. Schwartz closes her article with these words:

Although the face on Shakespeare's plays appears to be based on the queen's cartoon, lively debates contnue as to who wrote Shakespeare's works. Even as the computer aids in solving riddles, it continues to provoke them.

Schwartz appears to have hoped that she could show how the Droeshout was "based on" the image of the person who wrote Shakespeare's works. Since the evidence overwhelmingly shows that Shakespeare wrote the works attributed to him, it is something of a "riddle" that Schwartz never seems to have considered comparing the Droeshout to the bust of Shakespeare in his Stratford monument. It is also something of a riddle that the scaling she used for Leonardo was not the scaling she used for the Droeshout and Gower images (although, as we have seen, no possible scaling could make the features of the faces "match perfectly"). There are some riddles that even computers cannot help solve.